Republic of India

Overview

Importantly, India’s Constitution, Article 22(2), mandates that anyone detained upon arrest must appear before a magistrate judge within 24 hours of arrest or be released.

Importantly, India’s Constitution, Article 22(2), mandates that anyone detained upon arrest must appear before a magistrate judge within 24 hours of arrest or be released.

As of September 2014, in accordance with an order by India’s Supreme Court, all pretrial detainees in India who have remained in detention for over half of the maximum penalty time for their charged crimes must be released. It appears many of these detainees have still not been released.

Justice Bhagwati of the Supreme Court of India, quoting Justice Brennan of the United States Supreme Court, summarized the unjust results of the situation:

Nothing rankles more in the human heart than a brooding sense of injustice. Illness we can put up with. But injustice makes us want to pull things down. When only the rich can enjoy the law, as a doubtful luxury, and the poor, who need it most, cannot have it because its expense puts it beyond their reach, the threat to the continued existence of free democracy is not imaginary but very real, because democracy’s very life depends upon making the machinery of justice so effective that every citizen shall believe in an benefit by its impartiality and fairness.

General Status of Rights in India

India has been reported as having lengthy pretrial detention times—sometimes exceeding the maximum sentence associated with the criminal charges. Detention facilities generally are “frequently life threatening and [do] not meet international standards,” according to the 2013 U.S. State Department Human Rights Report for India. The report lists major problems as overcrowding and inadequate food, medical care, sanitation, and environmental conditions. Pretrial detainees are the largest population: “Persons awaiting trial accounted for more than two-thirds of the prison population.” Pretrial detainees are co-mingled with convicted criminals.

There are reports of arbitrary detention, physical abuse and torture. According to the Ministry of Home Affairs’ 2012-13 annual report, the NHRC registered for consideration 80,764 cases of abuse by security officials nationwide between April and December 2012. Commonly, national security laws and anti-terrorism laws have been used in India to allow excessive pretrial detention periods without trial or even adequate charges.

Due process of law is commonly disregarded, although there are individuals, agencies, and judicial authorities within India who are vigilantly pursuing increased rule of law and adherence to human rights standards. The basic legal framework exists to protect rights in India. Corruption, however, has infiltrated the judicial system and is reported as widespread. Much of the problem stems from overcrowding of prisons and overburdening of the judicial system. To remedy this, the Supreme Court ordered in September that the pretrial detention population be significantly cut down.

Pretrial detainees should be offered bail as a matter of right. Even in cases where bail is discretionary, the Supreme Court of India has held that bail must not be unreasonably withheld. (Babu Singh v. State of Uttar Pradesh, A.I.R. 1979 SC 527.)

The pretrial detention procedures, under the law (but not necessarily in practice), are as follows:

- A person is arrested and placed in police custody.

- Police custody is limited to 24 hours.

- Police custody beyond 24 hours must be approved by a magistrate judge.

- The magistrate judge must release on bail unless the investigation cannot be completed within 24 hours and the prosecutor has presented a well-founded case for detention.

- Extended detention is limited to 15 days. Bail should be granted as a matter of right except in “non-bailable” cases – typically serious offences with a maximum sentence of greater than 3 years. In non-bailable cases, an individual may only be released on bail at the discretion of the court.

- Any continued detention beyond this initial “well-founded” period. The magistrate must find “adequate grounds” for continued detention beyond 15 days, which may last up to a maximum of 60 days (or 90 days for charges carrying a 10 year sentence or more or the death penalty). Beyond 15 days, any detention must be in judicial custody, not police custody.

- Before expiration of continued detention of 60 or 90 days (and as soon as possible), the police must file a “charge sheet” with the magistrate. If no “charge sheet” is filed, the person must be released on bail, regardless of seriousness of offense charged.

- If a “charge sheet” is filed, the magistrate judge may determine whether to officially charge the detained person with the crimes accused and whether to deny or grant bail.

- Detainees are not required to testify to police officers while in custody.

- Many cases in India exist of pretrial detention that does not follow these procedures. These procedures set forth the legal guidelines, but do not reflect the daily practice in the country.

Domestic Laws Governing Pretrial Detention

Constitution

India’s Constitution (1950) guarantees fundamental rights that relate to pretrial detention. The following provisions are relevant, and apply to all “persons” in the country (not just citizens of India):

- Article 20(1) – “No person shall be convicted of any offence except for violation of a law in force at the time of the commission of the Act charged as an offence, nor be subjected to a penalty greater than that which might have been inflicted under the law in force at the time of the commission of the offence.”

- Article 20(2) – No double jeopardy. A person may only be prosecuted and punished for the same offence once.

- Article 20(3) – No person may be compelled to testify against himself or herself.

- Article 21 – “No person shall be deprived of his life or personal liberty except according to procedure established by law.”

- Article 22(1) – No person who is arrested shall be detained without being informed of the grounds for arrest as soon as possible.

- Article 22(1) – All persons arrested have the right to consult with and be defended by an attorney of their choice. This right shall not be denied.

- Article 22(2) – “Every person who is arrested and detained in custody shall be produced before the nearest magistrate within a period of twenty-four hours of such arrest excluding the time necessary for the journey from the place of arrest to the court of the magistrate and no such person shall be detained in custody beyond the said period without the authority of a magistrate.”

- Article 22(4) – Pretrial detention is limited to three months unless an Advisory Board finds there is “sufficient cause” for extended detention or the person is detained under Parliamentary order or law defining classes of detainees that may be held longer than three months (Article 22(7)).

- Article 22(5) – Anyone held in preventative pretrial detention must be informed of the grounds upon which they are being held and provided opportunity to appeal the decision.

- One exception to this (Article 22(6)) is that a prosecutor may choose not to disclose facts that are “against the public interest to disclose” (such as facts relating to an ongoing investigation that could result in destruction of evidence). This is a significant exception and has much potential for discretionary abuse.

Although the Constitution does not specifically state a right to a speedy trial, the 1979 Supreme Court decision of Hussainara Khatoon v. Home Secretary, State of Bihar held that “even under our Constitution, though speedy trial is not specifically enumerated as a fundamental right, it is implicit in the broad sweep and content of Article 21 [right to life and personal liberty].”

Code of Criminal Procedure

The Code of Criminal Procedure is the primary law governing pretrial detention procedures and rights. The Code prohibits arbitrary arrest or detention, but many reports of arbitrary arrest and detention exist. The State Department has reported that police even detain individuals without properly identifying themselves or providing arrest warrants.

Section 50 of the Code of Criminal Procedure requires the police to inform a person of the grounds for arrest at the time of arrest. The police must also inform the arrested person of their right to bail as a matter of course (for all “bailable” offenses).

Section 167 of the Code of Criminal Procedure requires investigations to be completed within 24 hours or for an arrested individual to be released unless the officer presents “well-founded” reasons to a magistrate to justify further detention. The magistrate judge has discretion to allow further detention of up to fifteen days. If the investigation is not completed within 15 days, extensions may be granted for up to 90 days if the charge carries a maximum sentence of 10 years or more or the death penalty and up to 60 days for all other crimes. After these periods, the person must be released on bail.

Section 436A of the Code of Criminal Procedure specifically aims to encourage release of pretrial detainees within a reasonable amount of time, specifically mandating that a person may not be held in pretrial detention beyond one-half of the maximum sentence of the crimes charged. This still could amount to an unreasonably long period of time for some individuals, but it at least draws a hard line for release. It provides:

Maximum period for which an under trial prisoner can be detained

Where a person has, during the period of investigation, inquiry or trial under this Code of an offence under any law (not being an offence for which the punishment of death has been specified as one of the punishments under that law) undergone detention for a period extending up to one-half of the maximum period of imprisonment specified for that offence under that law, he shall be released by the Court on his personal bond with or without sureties:

Provided that the Court may, after hearing the Public Prosecutor and for reasons to be recorded by it in writing, order the continued detention of such person for a period longer than one-half of the said period or release him on bail instead of the personal bond with or without sureties:

Provided further that no such person shall in any case be detained during the period of investigation inquiry or trial for more than the maximum period of imprisonment provided for the said offence under that law.

Explanation – In computing the period of detention under this section for granting bail the period of detention passed due to delay in proceeding caused by the accused shall be excluded.

The Supreme Court of India has directed that this law be applied immediately and pretrial detainees be released. (Vijay Aggarwal v. Union of India & Ors. W.P. (Crl) No. 32/2013 (5 Sept 2014).)

When assessing whether to determine bail—in situations where bail is not offered as a matter of right (minor offenses, typically with less than three years maximum sentence)—the Supreme Court provided these guidelines:

(1) The length of residence in the community,

(2) employment status, history and financial condition,

(3) family ties and relationships,

(4) reputation, character and monetary conditions,

(5) prior criminal record including any record of prior release on recognizance or on bail,

(6) the identity of responsible members of the community who would vouch for reliability,

(7) the nature of the offence charged and the apparent probability of conviction and the likely sentence in so far as these factors are relevant to the risk of non-appearance and

(8) any other factors indicating the ties of the accused to the community or bearing on the risk of wilful failure to appear.

Other Laws and Guidelines

Detainees should be allowed reasonable visits by outsiders. Detainees have the right to a lawyer. Charges must be made with reasonable particularity.

According to the U.S. State Department, the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (“UAPA”) of 1967 (am. 2008) denies bail for foreigners. Other state security laws are problematic by allowing “preventative detention” without charges or bail.

Other laws that have been used to justify extensive pretrial detention are the Chhattisgarh Special Public Security Act of 2005, the J&K Public Safety Act of 1978, the Prevention of Seditious Meetings Act of 1911, and the National Security Act of 1980.

International or Multilateral Treaties Concerning Arbitrary Detention

Universal Declaration of Human Rights

India is a United Nations member state and thus subject to the U.N. Charter and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

International Convention on Civil and Political Rights

India ratified the UN International Convention on Civil and Political Rights on 10 April 1979. India has not signed the Optional Protocol to the ICCPR, and thus complaints with the UN Human Rights Committee are not permitted. (India does, however, have its own National Human Rights Commission, which does receive prison complaints.)

United Nations Convention against Torture

India signed the UN Convention against Torture on 14 October 1997. It has not yet ratified the Convention. Many calls for ratification have been made. India has rejected attempts by the UN Special Rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment to visit the country.

Case Examples / Practical Observations

To file a complaint regarding pretrial detention, an individual must go through the local court system. The UN Human Rights Committee will not hear claims about India because India is not a party to the Optional Protocol to the International Convention on Civil or Political Rights. UN Special Rapporteurs, however, may independently investigate claims.

The prison system in India struggles to maintain basic human necessities for detainees. Information regarding conditions and populations at individual prisons is available in the National Crime Records Bureau prison report and on the U.S. State Department website.

Common Cause v. Union of India, (1996) 4 SCC 33

The Common Cause decision by the Indian Supreme Court brought great clarity to the maximum time periods within which detainees may be held. The Working Group on Human Rights has prepared an extremely helpful summary of pretrial detention rights resulting from this decision.

UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention Case Studies

The UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention released a report in March 2010 that itemized many instances of pretrial detention abuse in India. Included in the offenses were unjustifiably lengthy pretrial detention times, failure to provide due process of law, and physical abuse by the police. Of note, the Public Safety Act was the basis for detaining all individuals in the case study. This shows a willingness of the state authorities to use “public safety” as an excuse to detain without release on an indefinite period and without an arrest warrant. The Working Group noted that these cases constituted “serial detention” which amounted to an unlawful deprivation of personal liberty.

Local Organizations

State and national human rights commissions are available for prisoners to file complaints. The State Department reports, however, that the authority of the commissions is limited and they may only “recommend” that complaints be redressed. In addition, individuals or NGOs may also file public interest litigation petitions with the courts for Constitutional, public abuses, and other rights violations.

Many local NGOs are active in assisting individuals with issues of human and civil rights.

- Amnesty International

Amnesty International India leads a campaign called “Take Injustice Personally,” which aims to secure release of eligible pretrial detainees.

1074/B-1, First Floor 11th Main, HAL 2nd Stage Indira Nagar BANGALORE, KARNATAKA, 560 008

Tel: 91-80-4938-8000 - Working Group on Human Rights in India and the UN

G-18/1, Nizamuddin West, New Delhi – 110 013

Tel/Fax: 91-11-4054 1680

Email: contact@wghr.org - National Human Rights Commission (receives complaints of abuses of power)

Manav Adhikar Bhawan Block-C, GPO Complex, INA, New Delhi – 110023

Tel: 24651330

Email: covdnhrc@nic.in, ionhrc@nic.in - ActionAid India

- Asian Centre for Human Rights

- Citizens for Justice and Peace

- Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative

- FIAN India

- Lawyers Collective

- Partners for Law in Development

- People’s Watch

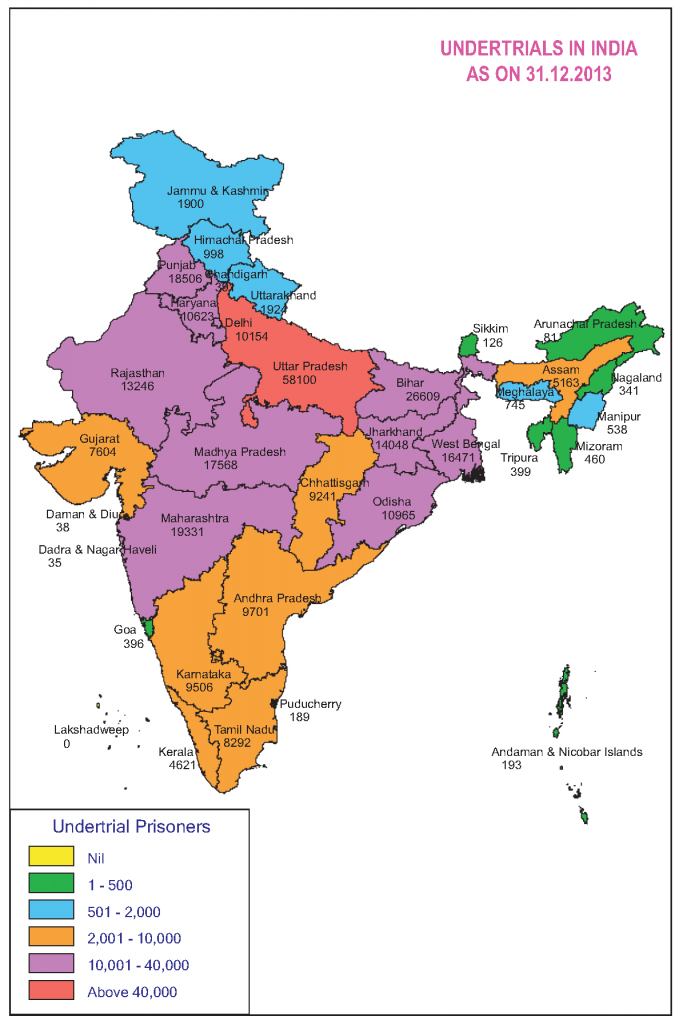

Statistics

The National Crime Records Bureau at the Indian Ministry of Home Affairs reports prison statistics annually. India’s 1,391 jails are overcrowded with an occupancy rate of 118.4%, according to the 2013 Prison Statistics report. Certain prisons (Delhi and Chhattisgarh) are overcrowded by more than 200%. The prison population as of December 31, 2013 is 411,992. 67.6% of this population is pretrial detainees – 278,503 persons were reported for 2013. Detention periods range from an average of 3 months (37.9% of detainees in 2013 were held for this length) to more than 5 years (3,047 pretrial detainees have been held this long).

According to Freedom House and the Working Group on Human Rights in India and the United Nations, “14,231 people died in police custody between 2001 and 2010, and approximately 1.8 million people are victims of police torture every year. This is likely an underestimate, since it only includes cases registered with the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC).”

Other Sources

Local prisons in India all should have built-in statutory oversight mechanisms. A place for pretrial detainees to complain and file requests for release. Although these mechanisms may not be always functioning, it is helpful to know they exist in order to seek out assistance once in prison.